A crowd of 50 or 60 people jeer as a Jewish shopkeeper tries to scrub antisemitic graffiti off the pavement.

Hats and broken glass are strewn all over the road in front of a destroyed Jewish-owned hat shop.

This is what six-year-old George Shefi sees outside his Berlin apartment building after the Nazi pogroms of November 1938.

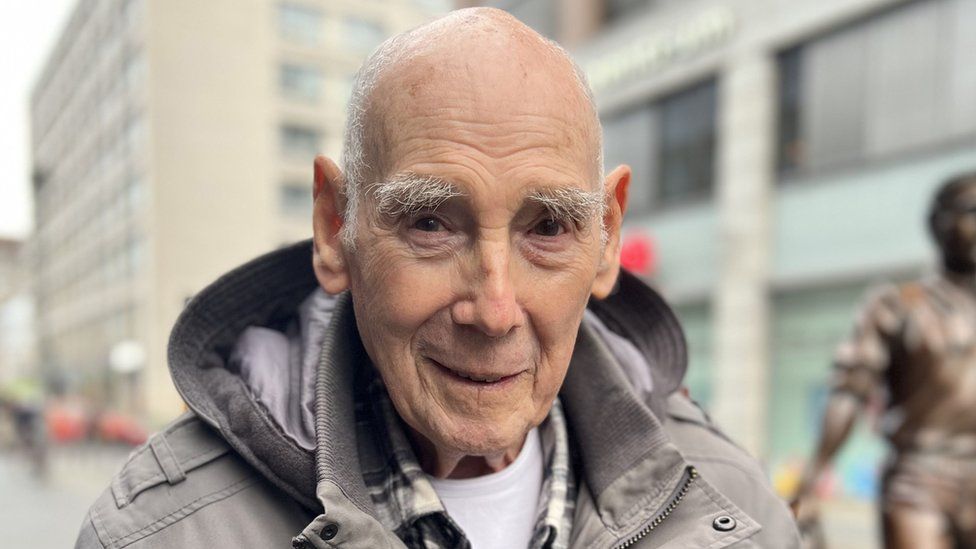

“I see still the picture in my mind, all the hats, and the glass, as if it was yesterday,” says George, who is now 92 years old and lives in Israel.

He fled Nazi Germany as a small child without his parents. He was one of about 10,000 mostly Jewish children evacuated to the UK after the attacks, in what became known as the British Kindertransport programme.

George has now come back to Berlin, in time for the 85th anniversary of the pogroms, to retrace his childhood journey of escape from Nazi Germany.

He remembers the smashed shops outside his home on Hauptstrasse in the Berlin district of Schöneberg, and being told not to go outside for a few days after the pogroms. He was shocked when he found out that his school, which was attached to a synagogue, had been burned to the ground.

But he didn’t know this was happening across Germany. And he didn’t realise that his life was about to change forever.

On the night of 9 November 1938, Nazi mobs rampaged across the country, destroying Jewish-owned shops and homes and burning almost all of Germany’s synagogues to the ground. Ninety-one Jews were murdered and 30,000 Jewish men were sent to concentration camps.

George’s mother Marie was fully aware of what was happening. This was the moment she made the painful decision to send George on his own to safety in the UK.

The November pogroms – sometimes referred to as Kristallnacht – marked a turning point in Hitler’s persecution of the Jews. After such brazen and uncontrolled antisemitic violence, German Jews suddenly realised they were not safe.

Those who could, left the country. Those who couldn’t, tried to get their children to safety.

By July 1939, Marie had managed to organise a place for George on the Kindertransport.

“My Mum said in the evening, ‘Choose your toys, you’re going tomorrow to go by train, you’re going to go by ship, you’re going to see another country, and another language. Marvellous!'”

George said his mother tried to make it sound like a fun trip. “An adventure!” he thought.

In the end, he couldn’t take any of his toys. The children were only allowed a small, sealed suitcase with basic essentials. Some children left only with a label marked with their name.

Marie took George to Berlin’s Friedrichstrasse station, where he got on a train packed with children trying to escape.

“It was horrible because all those people were parting with their kids,” he tells me. “I didn’t realise what was happening.”

“I could see her running along the platform trying to find me to wave goodbye,” George says. He could see her but because the train was so crowded, Marie couldn’t see him.

George didn’t know that this would be the last time he would ever see his mother. In 1943, Marie Spiegelglas was taken to Auschwitz concentration camp where she was murdered a few hours after her arrival.

The Kindertransport scheme was backed by the British state, but relied on NGO funding, donations and volunteers.

The British government waived visas for the children. But not for their parents. Most of them died in the Holocaust.

George says that for those children who escaped, it was traumatic arriving in England, and being selected by foster families you’d never met, and whose language you didn’t understand.

“It was like a cattle market,” he tells me. “If you were a young girl of five, with blond hair and blue eyes, you usually got a good family. If you were a kid of 17, and your nose is a little bit crooked, someone would take you in as a cheap domestic servant.” There was no oversight of foster families and some of those taken in later said they had suffered emotional or physical abuse.

At the site of George’s former school in Berlin, a wall of memorial stones in the playground commemorates local Jewish people murdered in the Holocaust, including Marie. George has come back here to talk to a class of 11-year-old German schoolchildren about his life.

“For a mother it must be really, really difficult. You put your child on the train, and you never see them again,” says one student, Tuana.

The children give George a present: a small box containing a fragment of tile, a remnant of his school building that was burnt down in the pogrom.

This is part of a journey in which George and two other survivors are retracing their steps and travelling by boat and train from their childhood homes in Germany to London’s Liverpool Street railway station, where Kindertransport children were met by foster families or relatives.

Organisers of this trip, such as Scott Saunders, believe that events like this are more important than ever, given what’s happening in the Middle East with the Israel-Gaza war.

“When you look at the world today, and you look at the growth of antisemitism, and the growth of hatred in all forms, whether it’s Islamophobia, whether it’s hatred of homosexuals, we have a responsibility to stand up and say: no, never again, must mean never again,” says Mr Saunders, founder and chair of March of the Living UK, a Holocaust education charity.

At the age of 13 George took another journey on his own, this time by boat to the US. When he was 18, he then emigrated to Israel, where he joined the navy and started a family. I ask George how he survived the trauma of loss and separation.

“I was lucky in life. Being on the Kindertransport and being kicked out of Germany isn’t luck,” he admitted with a wry smile. “But on the other hand, I met a lot of people who helped me, I got a good family, and I’ve reached the age of 92. So really, I can’t complain to that guy up there.”

George and his family have come back many times to Berlin to talk to people to make sure history is never forgotten, and never repeated.

On every trip they have a tradition: George has his photo taken at the same spot where, almost 90 years ago, he was photographed as a small boy – smiling, unaware of what was about to happen.

Later photos show him, back at the same place, defiant with his growing family. George Shefi’s children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren are his ultimate victory over Hitler.

Source : BBC