Please use the sharing tools found via the share button at the top or side of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach of FT.comT&Cs and Copyright Policy. Email licensing@ft.com to buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found here.

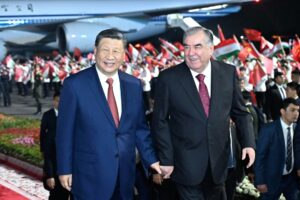

The writer directs the Center on the US and Europe at the Brookings Institution An eye-catching phrase in the UK’s most recent national strategy document — the awkwardly named “Integrated Review Refresh 2023” — notes that western allies increasingly agree that “the prosperity and security of the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific are inextricably linked.” Everything Everywhere All At Once would be an equally accurate description of the current geopolitical mood. And that is why Germany, while straining to help Ukraine defend itself against its Russian attacker, is currently racing to reduce its exposure to a disturbingly assertive China. Its most urgent concern: ratcheting tensions over Taiwan, amid surging chatter of a US-China war. Germany’s foreign minister Annalena Baerbock, just back from a visit to Beijing, said a military conflict over the island would be a “horror scenario”. Indeed. The Rhodium Group, an economics and policy research firm, recently estimated that the global economic disruptions caused by a blockade of Taiwan could put “well over $2tn in economic activity at risk, even before factoring in the impact from international sanctions or a military response”. For Germany, one of the world’s most globalised economies, the effect would be akin to being struck by a meteorite. Next on the worry list is Beijing’s double game in Ukraine. In a long-delayed phone call on Wednesday with Ukraine’s president Volodymyr Zelenskyy, his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping pledged his commitment to sovereignty and territorial integrity, and warned against nuclear wars (att’n Comrade Vladimir). Beijing has a keen interest in establishing itself as a peacemaker, and even more so as a rebuilder of Ukraine — especially if that comes at the expense of Kyiv’s western supporters. At the same time, China has deepened its economic leverage over Russia, and discreetly endorsed Kremlin positions. Xi let himself be feted for three days on a state visit to Moscow in March. And then there are the everyday headaches of growing Chinese interference in Europe: lectures and threats from Chinese diplomats, unfair trade practices, espionage, disinformation — and, lately, secret “shadow police stations” keeping tabs on Chinese expatriates. Cue a peculiarly German sign of genuine alarm: a storm of China papers. The country’s first-ever national security strategy, promised by the traffic light coalition on its accession in December 2021, continues to circle over the cabinet table in a slow holding pattern; there are credible rumours of a late May landing. Draft China strategies have, however, leaked out of both the foreign and the economics ministry. Three mainstream parties (CDU, SPD, Liberals) have published their own documents; the Greens have not, but they helm the foreign and economics ministries, and are anyway in the happy position of being able to whisper “we told you so”. All four converge on a notably hardened take on Chinese state capitalism and aspirations for global dominance. Yet Germany’s Beijing dilemma remains very real. China is its most important trading partner, ahead of the US. Berlin managed, with tremendous effort, to decouple from Russian fossil fuel in 2022. A full decoupling from China, in comparison, would amount to economic vivisection for Germany and indeed the rest of Europe. But then no one is advocating that, contrary to blaring complaints from some sectors of industry and the China lobby. The order of the day is “de-risking” (reducing dependency, especially in critical sectors of the economy like technology and rare earths) and deterring or defending against harmful Chinese actions. That sharper take is leading Berlin to re-examine, among other things, the recent plans to sell a minority share in a Hamburg port operator to the state-owned Cosco conglomerate, and the role of telecoms equipment from Chinese suppliers Huawei and ZTE in German networks. More is needed — especially given upcoming German-Chinese consultations in Berlin in June, and discussions of European China strategy at an EU leaders meeting shortly afterwards. The transatlantic alliance, the EU, and the member states, so effective in standing up to Russia together, have presented a sorry picture of disunity on China. But the blueprint has now been provided in a remarkably hard-hitting speech by EU Commission president Ursula von der Leyen. As for Germany’s China lobby, which according to reports includes two former cabinet ministers, it has (unlike its Russian equivalent) never been comprehensively mapped. Perhaps it is time for that.

Source : Financial Times